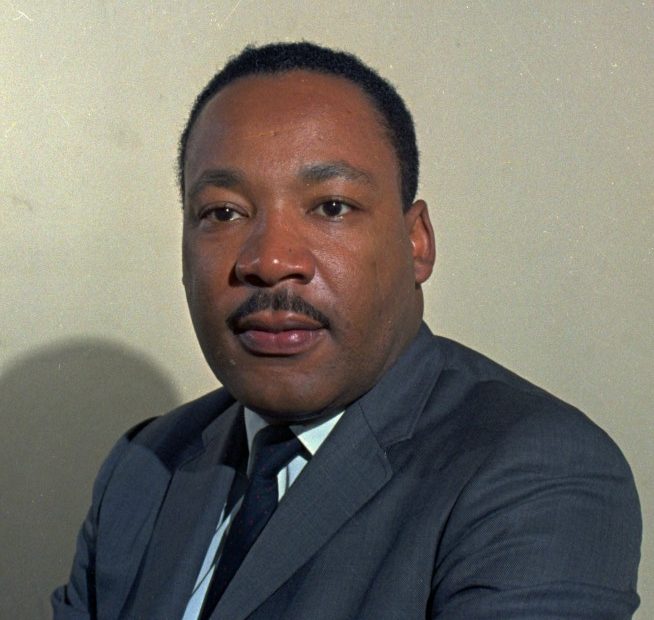

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) — An Alabama motel that was featured in “The Negro Motorist Green Book” and provided a home for Martin Luther King Jr. during civil rights demonstrations in the 1960s is being transformed into the centerpiece of a new national monument.

Long vacant and in disrepair, the 65-year-old A.G. Gaston Motel is being renovated as part of the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, established by former President Barack Obama in 2017, long before the “Green Book” gained recognition in the Oscar-winning movie of the same name.

Workers performing the refurbishment, which is part of a $10 million downtown project, are shoring up masonry damaged by decades of weather and removing later additions to the motel. Leaves and trash rustle in halls where doors stayed open for who knows how long; windows and electrical outlets are missing elsewhere.

“It’s in terrible shape now, but it’s structurally sound,” said Rogers Hunt, who is overseeing the initial work.

Opened by the late black businessman A.G. Gaston in 1954 in a city that was infamously segregated, the two-story motel provided top-notch accommodations that included nicely furnished rooms, a restaurant and a lounge that was a gathering spot for the black community.

The motel was a haven for African American travelers who used the “Green Book” to find friendly, safe accommodations during the worst days of Jim Crow. Its guests were said to include Aretha Franklin, Duke Ellington and Harry Belafonte.

“This was a state of the art hotel whether you were black or white,” said James Poindexter, 87, who works for Gaston’s construction company and is a superintendent of the current job.

The motel eventually closed and was reconfigured into apartments that make the original rooms difficult to envision.

The large room where King lived in 1963, when authorities used police dogs and fire hoses against black demonstrators seeking equal rights, was later subdivided into two rooms, Hunt said. A bomb went off outside the motel after King and others held a news conference about desegregation efforts that year, but the building survived.

Hunt said workers will restore the Gaston Motel to the way it looked in its “Green Book” prime, down to trying to find new door frames to match original steel ones that had a distinctive groove down the side.

“We have the original plans to go by,” said Hunt. He, like Poindexter, works for A.G. Gaston Construction.

For more on the legacy of the Green Book hotels, check out the AP’s “Get Outta Here” podcast.