WASHINGTON (AP) — As she nears a decision on whether to seek the presidency, Sen. Kamala Harris is taking on what could be a hurdle in a Democratic primary: her past as a prosecutor.

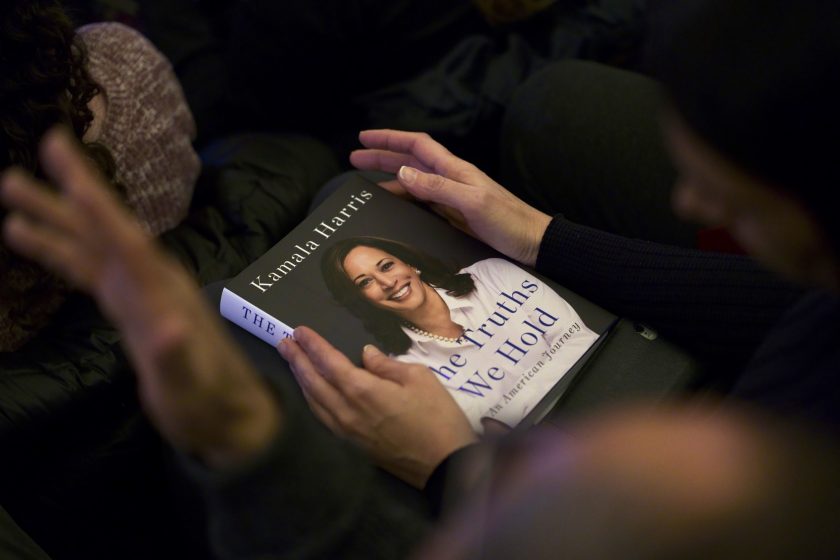

In her memoir published Tuesday, the California Democrat describes herself as a “progressive prosecutor” and says it’s a “false choice” to decide between supporting the police and advocating for greater scrutiny of law enforcement. The argument is aimed at liberal critics of her record who argue she was sometimes too quick to side with the police and too slow to adopt sentencing reforms.

“I know that most police officers deserve to be proud of their public service and commended for the way they do their jobs,” Harris writes in “The Truths We Hold.” ″I know how difficult and dangerous the job is, day in and day out, and I know how hard it is for the officers’ families, who have to wonder if the person they love will be coming home at the end of each shift.”

But, she continues, “I also know this: it is a false choice to suggest you must either be for the police or for police accountability. I am for both. Most people I know are for both. Let’s speak some truth about that, too.”

After high-profile fatal shootings involving police officers and unarmed people of color, the criminal justice system’s treatment of minorities is a top issue among Democratic voters. The passage suggests Harris is aware that her seven years as the district attorney in San Francisco, followed by six years as California’s attorney general, is something she will have to explain and signals how she may frame her law enforcement career if she decides to run for the White House.

“It’s a presidential campaign, and every aspect of a candidate’s record is going to be scrutinized and they’re going to have to answer for it,” said Mo Elleithee, a longtime Democratic operative who leads Georgetown University’s Institute of Politics and Public Service. “She knows that this is something that’s heading her way and a good candidate is one who doesn’t wait for it to hit them. A good candidate is someone who addresses it proactively, and she appears to be doing that.”

Beyond the book, Harris supported legislation that passed the Senate late last year and overhauls the criminal justice system, especially when it comes to sentencing rules.

In the book, Harris recounts an instance when she was an intern at the Alameda County district attorney’s office and an innocent bystander was one of many people arrested during a drug raid. Harris said she “begged” and “pleaded” on a late Friday afternoon for a judge to hear the case so the woman could avoid spending the weekend in jail.

Kate Chatfield, the policy director of the California-based criminal justice reform group Re:store Justice, said Harris did do “some good” when she was in law enforcement, but that it was “incumbent on the public to hold her accountable for the ways in which she either didn’t do enough or actually did some harm.”

“When the conversation shifts, one should be expected to be questioned about those choices,” Chatfield said, noting among other issues Harris’s advocacy for tougher truancy laws.

By addressing policing in the book, Harris is taking on an issue that confronted Democrats and some Republicans in 2016. Democrat Hillary Clinton was criticized for her husband’s role in passing the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which created stricter penalties for drug offenders and funneled billions of dollars toward more police and new prisons.

The issue is likely to be the subject of fierce debate in 2020 as well and could expose divisions among the wide field of candidates — presenting hurdles for some and opportunity for others.

Former Vice President Joe Biden was the head of the Senate’s Judiciary Committee when the 1994 crime bill — which is now criticized as having helped create an era of mass incarceration — was passed and signed into law, which could be an obstacle for him. New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker was central to the passage of the Senate’s criminal justice overhaul package and is certain to tout it if he decides to launch a presidential campaign. Meanwhile, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who is also considering a 2020 bid, often refers to her own prosecutorial past.

The memoir — and the publicity surrounding it — will shift the 2020 campaign spotlight to Harris this week after much of the focus has been on her Senate colleague Elizabeth Warren. Last week, the Massachusetts Democrat became the most prominent person yet to take steps toward a presidential run by forming an exploratory committee. Her weekend trip to the leadoff caucus state of Iowa also generated largely flattering headlines.

Some criminal justice advocates said they were happy the issue would get more attention in 2020.

“When we had the 2016 elections, it was at the height of Ferguson and Baltimore, and we still didn’t have serious engagement with criminal justice reform,” said Phillip Atiba Goff, the president of the Center for Policing Equity, referring to the protests that followed the deaths of black men at the hands of police officers in Missouri and Maryland. “My hope is that we require candidates to demonstrate that they know more than the catchphrases of the activists in their bases.”

Surveys underscore the potency of criminal justice issues among Democrats. A February 2018 poll conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that majorities of Democrats — but far fewer Republicans — think there’s been little progress for African-Americans on criminal justice or policing issues over the past 50 years. The poll showed that 45 percent of Americans, including 62 percent of Democrats and 19 percent of Republicans, thought there had been little to no progress on fair treatment for black Americans by the criminal justice system. Similarly, 46 percent of Americans, including 63 percent of Democrats and 23 percent of Republicans, said there’s been little to no progress for African-Americans on fair treatment by police.

While it’s not yet clear how Harris’ prosecutorial background could affect her primary bid, it could help her if she faces President Donald Trump in the 2020 general election.

“He ran as the law-and-order president,” Elleithee said of Trump. “Being able to go toe-to-toe with him on law and order in a smarter way, I think, is going to be important. Should she win the nomination and does it by navigating this topic well, then I think she would be a strong voice and a force to be reckoned with when it comes to issues of law and order, criminal justice and civil rights as they collide in a general election.”